Anyone interested in reducing their environmental footprint on our beloved planet as probably considered ways to stop or reduce their flights by plane.

Examples of lifestyle choices

One of my friends who works as a speaker and facilitator in sustainability has reduced her footprint significantly by hopping on a plane only once in the past thirteen years. Based in Europe, she has enjoyed giving her talks by taking trains. The only time she flew was to go visit her family in Asia. One of the strengths I see in her is her ability to say NO and to stick to her values. She has refused on several occasions to give talks for companies that didn’t align with her values (although they paid really well), or if they required her to fly.

Another of my friends, who is also a speaker, author and innovator in the field of sustainability, reminded me of the notion of karma. I was interested in seeing the bigger picture. When asked what he thought about flying, he reminded me that depending on our intention, the results we create will be different. Are we taking this flight to be of service, or to avoid a situation we don’t like? Are we flying with our intention anchored in a place of love and trust or from a place of fear and greed?

What is flying anyway?

Flying is nothing short of a miracle…

First things first:

Geologically, it took between 50 and 300 million years for our planet to form crude oil.

Technologically, it took humanity 1.7 to 2.0 million years of evolution to move from domesticating fire to the capacity to transform crude oil into kerosene, which was invented in 1854, and for the Wright brothers to conduct the first flight in 1903.

While flying has become more popular today, and is expected to grow in the next decades, it remains an activity for a small minority of the privileged few. It has been estimated that roughly 6% of humans on the planet has been on an airplane (source).

When it comes to curbing climate change, air traffic represents 2.5% of global CO² emissions, and 4% of global warming. The difference is due to other emissions such as nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide (NOx), contrails, sulphur oxides (SOx), particulate matter, soot, among others. Furthermore, as demand increases and other industries decarbonize, the aviation industry could be responsible for up to 22% of global CO² emission.

The individual/collective paradox

From an individual perspective, some of the most effective steps you can take to reduce your CO² emissions are the following:

- Transition towards a more plant-based diet. (The meat and dairy industry are responsible for 14.5% of global gas emissions)

- Conduct an energy audit of your home, and find ways to transition towards renewable energies.

- Drive less, commute with public transportation or car-sharing, rather than being on your own in your car

- Reduce the number of flights you take

Other recommendations have been mentioned by Columbia University in this article.

Whatever emissions you can’t/aren’t willing to reduce, you can offset CO² emissions. (I donate to a non-profit that plants trees in India, Haiti, Kenya and Namibia. Here is a list of best carbon offsets for individuals).

For most people, these changes seem unappealing.

I remember two years ago when I attended an event at the GoodPlanet Foundation near Paris, where I heard speakers and sustainability influencers talk about their low-carbon holidays canoeing in Ardèche in the South-East of France, or hiking in the mountains. I felt some contempt thinking: “What kind of holidays is this?”

I was used to travelling in South-East Asia, visiting the Petra temple and the Wadi-Rum desert in Jordan, and other exotic destinations (although some were coupled with business travel where I flew business class, emitting close to 3x the CO² of an economy seat).

I experimented with a 0-flight policy for one year, which felt like a big deal for me.

It actually made my life much easier.

I did miss out on opportunities:

I said no to attend one of my good friends’ wedding in Lebanon

I said no to teach a class on sustainability in Morocco (getting there by train and ferry would have been too much of a hustle from Paris, and I do have so say that I already had a full schedule. I also thought that if they found a local person to teach the class it would be more sustainable on the long-term.)

I declined attending the annual meeting in the U.S of a non-profit of which I was a board member.

But I felt in integrity, and grounded. I lowered my carbon footprint to about 8 or 10 tons of CO² that year, the average for a French citizen. (To calculate your footprint, use an online calculator. Here are some popular ones: UK, US, France).

I sustained my no-flight diet for 2 years. It felt like a real detox and I didn’t miss flying anymore.

I was proud of my net impact: no flights, almost vegan diet, teaching classes on sustainability. Pretty good net impact.

After a while, I felt a deep longing to return to India, a country dear to my heart and Soul. After much resistance, and thanks to the encouragement and support of people around me, I booked some tickets and took two weeks off. It was amazing. That is when I realized the miracle of flying.

The bigger picture: the importance of systemic change and reflections on net impact

I also questioned the validity of simply reducing one’s footprint. Yes, there is the need to minimize our individual footprint. What about the responsibility of companies to offer us solutions for cleaner travel?

The paradox is that now matter how much you reduce your footprint individually, if others don’t “play the game”, we are doomed. We need to play this game collectively: with corporations governments and NGOS.

But what about the idea of net impact?

Is it the same to fly if you are just going to lie on a beach, or if you are going to bring positive impact where you go? Could that positive impact be delivered by someone else locally?

These are questions to bear in mind when deciding whether to fly or not.

As for the aviation industry, so far, it has started working on the issue.

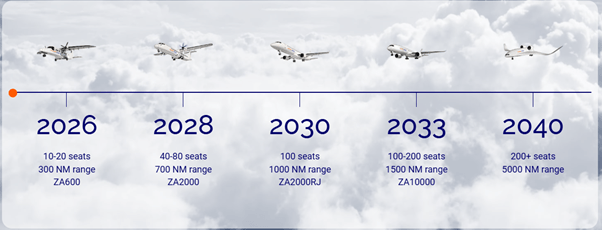

As I explained in another article, aircraft manufacturers are already developing aircrafts capable of transporting passengers with minimal impact. For instance ZeroAvia has announced a timeline for the development of their Powertrain models:

Source: ZeroAvia

Other innovations such as Airbus’ ZEROe have been delayed. Initially planned to be delivered by 2035, the delay could push this hydrogen-based aircraft to fly commercially by 2040-2045. In the meantime, Airbus is focusing on the company’s Next Generation Single Aisle destined to replace Neo and thus saving 25% of CO² emissions thanks to fuel efficiency.

If you have thoughts and reflections on these topics, I’d love to hear from you. Feel free to post below.

To dive deeper into the carbon footprint, read the following: